- Home

- Curtis White

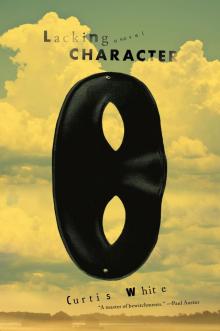

Lacking Character

Lacking Character Read online

Praise for the novels of Curtis White

“White’s work has a surrealistic, hallucinatory quality. More specifically, it’s absurdist in the tradition of William Burroughs, Joseph Heller, and Terry Southern.”

—Harvey Pekar, The Austin Chronicle

“White is a mischievous and omnivorous griot for the digital age…White wants readers to take stock of the timbre, texture and content of our times, and to ask, ‘What have we learned? What have we lost?’”

—Donna Seaman, The Chicago Tribune

“Witheringly smart, grotesquely funny…so moving as to be wrenching.”

—David Foster Wallace

“Curtis White writes out of an admirable intellectual sophistication combined with viscerality, pain, and humor.”

—John Barth

“Curtis White’s fiction presents a scintillant, ironic surface, one that is barely able to contain the bleakness of American fin-de-siècle exhaustion, which latter is his essential theme.”

—Gilbert Sorrentino

LACKING CHARACTER

Copyright © 2018 by Curtis White

First Melville House Printing: March 2018

Melville House Publishing

46 John Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

8 Blackstock Mews

Islington

London N4 2BT

mhpbooks.com

facebook.com/mhpbooks

@melvillehouse

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: White, Curtis, 1951- author.

Title: Lacking character / Curtis White.

Description: Brooklyn : Melville House, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017045497 (print) | LCCN 2017051527

(ebook) | ISBN

9781612196794 (reflow able) | ISBN 9781612196787 (softcover)

Subjects: LCSH: City and town life–Fiction. | BISAC:

FICTION / Humorous. |

FICTION / Literary. | GSAFD: Humorous fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3573.H4575 (ebook) | LCC PS3573.

H4575 L33 2018 (print)

| DDC 813/.54–dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017045497

ISBN 9781612196787

ISBN 9781612197357 (library edition)

Ebook ISBN 9781612196794

Ebook design adapted from printed book design by Betty Lew

v5.2

a

For Nicolas

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

1.

—after E.T.A. Hoffmann

What follows is a story of contagion, and it begins, as all such stories must, with a message both obscure and appalling.

The city in which this message was passed was the city of N— in the geographic center of Illinois, and, as the saying goes, in the middle of nowhere. N— was notable as a place that had succeeded in achieving the destiny American cities had sought for centuries: complete abstraction. As the German mystic Jacob Boehme once observed, “It is not philosophers who are abstract, it is the man in the street.” Actually, this story with its embedded message happened at least three times, in various places, but on the same spring date, as if this world were only a quarrelsome device like one of those old brightly painted tin toys that you’d wind up and watch as a dog jumped on a wagon and back, on a wagon and back, in that false infinity provided by winding a spring tightly.

The first time it happened was in 1810, in Dresden, as later attested to in a most remarkably vivid account by the gnomish writer of realist fantasy E.T.A. Hoffmann, in his story “Mademoiselle de Scuderi.” Then it all fell out again in 1910, in Paris, on the edge of the first modern war. Picasso and Braques were hanging out, drinking yellow-green absinthe, and then enjoying hallucinations at that new sensation, the Bijou, the florid cinema. While they enjoyed such bohemian pleasures, the second coming of these remarkable events lit the air around their heads, the most brilliant heads of a most brilliant time, but, sadly, not even they noticed. They were painters, after all, and perhaps not open to the “unfolding” of things across vast stretches of time. That I know of, there is no record of the events happening elsewhere either (although I once imagined, wrongly as it turned out, that there were cryptic allusions to them in Franz Kafka’s story “The Warden of the Tomb”). The third time that this story unfolded itself, as if the very air could open up like a Chinese paper box, was in 2010. Then, the residents of one house in N— were awakened from that self-satisfied sleep of the Midwest by a mad pounding at the door.

As it happened, all the women of the house were away sex-touring and ganja-smoking in Jamaica. The men had been left behind with strict instructions to lock the doors and ignore the baying of hounds. The men wondered if this pounding at the door was what the women meant by “the baying of hounds,” so they went cautiously to an upstairs window.

“Open the door, for God’s sake, open the door,” a man’s voice said, rising up above the sublime pounding he was giving to the door.

“Who is down there?” the men asked. “We know better than that, Mister. We were warned not to open the door to strangers.”

“I must speak to the Marquis!”

“The Marquis? I think you have the wrong house. Try that big one at the end of the block.”

“For God’s sake, it’s a matter of life and death. I stand falsely accused…of an atrocity.”

“Well, why didn’t you say so?!”

And down they went and unbolted the great oak portal.

No sooner had they opened the door than a figure wrapped in a flowing black cloak burst through violently, eyes wild, a man with the intensity of a demon!

“It’s no wonder that you’ve been accused of an atrocity. Just look at yourself!”

The men now thoroughly regretted opening the door. One of them said, “Why don’t you come back tomorrow at a decent hour?”

“Does destiny care for the time of day?” the man in the black garb asked.

They had no opinion on the matter.

“Why, then, if you won’t take me, take this, and give it to the Marquis.”

And he held an envelope aloft.

2.

“Childe Harold bask’d him in the noon-tide sun,

Disporting there like any other fly…”

—BYRON

When I try

to picture him, the caped stranger looks a lot like Guy Williams in the old TV show “The Lives of Zorro,” minus the mask. Oh, hell, let’s give him a mask then. They’re not expensive. You can get a bag of ten for a dollar-fifty at the Penury Factory Outlet down in Heyworth. So, if he wants a mask, vamos!, for God’s sake. So, he’s wearing a mask and one of those sexy flattop fedoras that I thought were simply the coolest thing in the world circa 1959. It even had a brightly wrought sterling silver band around it, if I’m not mistaken, although I might be thinking of Richard Boone’s Paladin.

At any rate, this masked character at last got around to taking out an envelope in which was the note with the famous message he’d been promising.

“Take this letter to the Marquis. It is a matter of life and death—my death!”

One of them, let’s call him Rory, stepped forward to say what all the others were thinking. “Sir,” he said, “no offense, but this is not making a whole lot of sense to us. We have no idea who you are, there is no Marquis here—and, to tell you the truth, we’re not collectively clear on just what a Marquis is—and you’ve frightened us a lot with your bizarre aspect. So, you might as well tell us what’s in the envelope because we’re just going to open it as soon as you leave.”

The stranger looked perplexed, angry, frustrated. Perhaps he was a man with black belts in various martial arts, or a mob enforcer, perhaps he was Special Forces, a Navy SEAL, or someone with a lot of PTSD issues including the habit of savage resolution to situations that are not quite going his way. He waved the letter dramatically over his head—he was wearing really gorgeous black gloves, the softest calfskin, that went down his arm nearly to the elbow.

“I can tell you this: my letter comes from a woman of great power and influence living in a villa in the Hebrides. Have you never heard of the famous Queen of Spells? Surely, even in this depraved outpost of humanity, you have! I believe her letter touches on issues related to the flowing light of the Godhead. In this letter there is a vision of a great marble slab that lies at the base of a mighty mountain. There is a doorway in it like the doorway to a great city. A radiance as bright as that of the sun overflows the marble.”

“Are you making this shit up?” asked one ruffian.

“Well, if that is not convincing to you, consider this,” he said, and he turned and flung open the door.

The men looked out and saw that in the courtyard before their house hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Zorro-like guys were riding on small black horses—no more than two feet tall—rearing often and dramatically on their hind legs, as if the movie they were in was almost over and they were thinking about riding into the sunset. The men also waved envelopes—not Stetsons—high over their heads, messages galore. There they were in their pitchy vestments, as if the computer-graphics geeks had gotten carried away, gone a little haywire, in this scene. The men and horses roiled—anxious, trapped—and looked upon one another as if they were as terrified by this vision as were those who looked upon them. Stranger yet, they were crying great confused tears that flowed down their faces and seeped out beneath their little masks. But for what reason? That was what was so hard to say.

“This, this, is the reality that you scorn, on which you dare to look with your doubt and cynicism. Now, forthwith, to the Marquis!”

The men were overwhelmed by what they’d seen. They dropped their pretense and took the man directly to the Marquis.

3.

“We may lose more than 300 million people. So what? War is war. The years will pass and we’ll get to work producing more babies than before.”

—MAO

The men took the message to the Marquis in his chamber, the place where the critical issues of state were decided. The men said, “We are most sorry to disturb you, your Excellency, but this caped man has come on horseback to our door and insisted on delivering this message to you.”

The Marquis looked up and said, “Well, it had better be important. I just achieved a new level in Halo.”

“Really? You play Halo?”

He sighed.

“I play Halo to excess. Some days I think I am become Halo. Sometimes I can feel the numbers, the digits, flowing like fine sand in my head.”

Although he was called the Marquis, he was usually just a regular guy, one of the boys, a dude, if you will. He liked to watch football on Sunday, and he was fond of racial slurs. He did all-nighters with his aristocrat pals over the Xbox. At his hands the aliens died in their legions. As for the business of state, it was often neglected. Of course, sad people lined up outside the Marquis’s villa with sad faces and waited to petition him, but he rarely put in an appearance. Not because he didn’t care, but because it took so long. “Seriously,” he’d say, “those people have a lot of problems.”

On the rare occasions when he did go outside to speak to his people, he usually ended up sitting on the curb with them and passing out little sandwiches and fruit juice. Invariably, he’d be so incensed by their unjust fates that he’d fire half his staff and spend days reforming the entire social and economic structure of his domain from the top down. Eventually, though, his longing for the game, the comfort he felt in the presence of the little aliens, would overcome him. He’d go back inside, and it would be months before he’d come back out. Only the pizza boys would be allowed in the courtyard. He’d re-hire the staff, and apologize to the industrialists he’d sent to jail, and promise not to interfere with their “important work” again. The people would simply return to being sad, which wasn’t so bad, really; it seemed very natural for them. They were “good at it,” as he said.

Strange as this may sound, he convinced himself that in killing these digital aliens in Halo, he was making an important contribution to the welfare of the people. At least it felt that way. At least he knew that his people did not have to worry about the sneaky little aliens. That problem he had put to rest, so sleep well, my people.

“What level are you going to?”

“I finally achieved the Heroic level.”

“That’s good,” said Rory, “I’ve been beyond it, but that’s pretty good.” Rory served as the Marquis’s amanuensis, so you’d think he’d know how sensitive his employer was about his virtual accomplishments.

The Marquis gave him what we used to call a dirty look, back in those forgotten days before emoticons when people exchanged facial expressions. If you’re having trouble imagining what a dirty look was like, I can only assure you that this one was absolutely dirty, so dirty that Rory was frightened to look back at the Marquis and averted his gaze to a water-stained corner of the ceiling. Fortunately for Rory, while the Marquis wasn’t used to trash talk, he was kind enough to “cut him slack,” as humans once said, back when they actually said things.

“I may not be a Halo Legend,” he intoned, looking down his noble nose, “but I am still the Marquis.” Rory got the point.

“So you beat the parasitic Flood when it slipstreamed into New Mombasa and launched a melee?” he said, with desperate enthusiasm.

Another said, “That’s like where the aliens capture a redoubt and the ugly, vicious things just start pouring forth…”

“…like a replicating virus,” said a staff member named Ted, who will now be retired from this narrative on a permanent basis. He’s served his purpose, said his line, and now may leave.

“Wow, can you really handle that heavy stuff, your Illustriousness?” asked Rory. This used to be called “eating shit” back in the day, before our avatars did all the shit-eating for us, although once again you’ll have to take my word for it.

The Marquis continued, meditating on something bizarre. He said, slowly, “Yes…replicating virus. A contagion. They did pour forth, you are quite right. But they weren’t the usual sneaky aliens. Thousands of little men dressed in black and on horseback poured out from what looked like a large wicker clothes hamper that someone had abandoned in a backyard. They were dressed sort of like Zorro, if you remember him (of course you don’t), or tiny versio

ns thereof. Zorro was…never mind. The strangest thing was that they were weeping. They were milling around in confusion and bewilderment, not really attacking anything at all. Their weapons seemed to be little plastic swords. I thought something was wrong with the game, but once I started nailing them, that thought was beside the point. I took them down one after another. They gave out this little squeaky scream when they died. It was amazing and very satisfying.” He grinned. “That’s how I amassed points to become Heroic. Actually, it happened in just the last hour.” In spite of what he was revealing, he seemed pleased with himself, as if he really had done something heroic.

“The one thing that surprised me was that each of the little men seemed to be subtly different from the others. It was as if, had I looked at one closely enough, I would have discovered a real individual little life there. I can’t tell you what a charge that thought gave me as I slaughtered them. In fact, it even gave me an incipient hard-on. Sorry, I don’t know how else to put it. What I mean by ‘incipient’ is that it was far from my Toro Furioso, you know, with the veins black and twining about the thick neck of the beast. It was more just something between me and the little men. A sort of intimacy in death. A sort of softish thinking about being a hard-on but with no clear idea about why I’d need one just then. Do you know what I’m talking about? Well, why don’t we agree, just among ourselves, to the idea that the little black men I slaughtered were individuated and that they caused me to have a hypothetical hard-on, a propositional, presumptive, or conjectural hard-on, a hard-on in potentia, as Aristotle would have put it.”

Lacking Character

Lacking Character